How young children see the world

Young children take time to learn whether things are living or non-living, real or pretend. In their world these categories are not yet well defined. It may make for a world that has more exciting, even magical, possibilities but it may also at times be more bewildering, frightening or threatening.

Adults bring to picture books a well-defined set of understandings about how the world works and how the picture book format interprets experience. It takes considerable time for a young child to acquire a similar kind of understanding and ‘background’ knowledge.

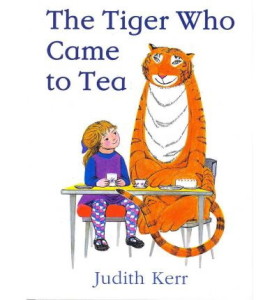

They may know, for example, at one level that illustrations aren’t real and that they represent things from the real world. But at another level they believe that the characters or animals in their books are real. ‘Where did the tiger go?’ asked a boy at kindergarten yesterday when I had just finished reading The Tiger who came to tea. For him, that tiger was out there somewhere. He might even come to visit his house and stay for tea!

Young children take time to learn how illustrations represent things. Adults understand that a partial illustration or a side view of, say, a fox represents the whole fox. A child on the other hand will ask ‘Where are his other two legs?’ and turn over the page to see if they are on the back of it. When I was reading Noah’s Ark to my daughter, Juliet, many moons ago, she thought the ostrich, who had only one leg showing, ‘must have his other leg at the animal hospital where they fix legs.’ (I only remember this because I kept a diary of our reading when she was three until she turned five.)

‘What’s the matter with Mary Jane?’ from When we were very young by A.A. Milne. Illustration by Ernest H. Shepard

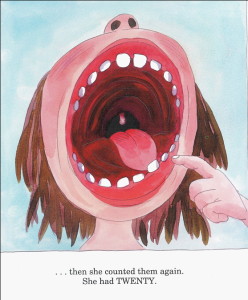

From I want my tooth! by Tony Ross (A Little Princess Story)

A child’s background and experience can also colour what they see. As a child I was sure that the thing buzzing around Mary Jane’s head was a fly. As an adult I came to realise it was her shoe she’d kicked off because of that rice pudding. This had never occurred to me as a way of venting my frustrations as a child though I am sure I hated rice pudding just as much as Mary Jane.

Size in illustrations is another convention that needs to be understood. Children do not always recognise the rules of perspective, for example. A figure who is small and a long way off may, in fact, be larger than a figure in the foreground. Very confusing if you don’t know the rules.

From The Helen Oxenbury Nursery Rhyme Book. Er . . is that a real horse?

Size is also used for other purposes than representing reality in children’s books. It can draw attention to something as does this wonderful illustration from I want my tooth by Tony Ross. The Little Princess’s mouth and teeth fill the left hand page yet on the facing page her mouth is the same size as everyone else’s. Size exaggerates, distorts, creates fear – it achieves all sorts of things in picture books. Children respond enthusiastically to these techniques without necessarily understanding them.

Young children will not yet know the meaning of many of the words they hear when listening to a story. They may not understand enough to ask for meanings and it may take time for them to recognise what they don’t know and to learn how to ask. This plays some part in why children love to hear the same story over and over. As you know, young children love repetition, rather more than you do! ‘Repetition Rules’ has more to say on this subject.

Knowing that each part of a story contributes to the whole takes time for a child to appreciate. It isn’t immediately obvious to a child that a story has a beginning,a middle and an end. After all, many of their earliest board books are not structured in this way. For reasons of their own, young children may be more impressed with parts of a story or its pictures than with the story as a whole.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children need time to come to grasp the concepts that shape what we hear and see which we take for granted. They will find their own way, and they don’t need to be hurried, but it does help if we can support them along the way by understanding the complex processes involved.

Do these observations chime with any you have made? Comments most welcome.

Future blog topics: Please send any topics you’d like me to talk about either by posting here or by emailing me your thoughts (gibbs.donna@gmail.com/).

Recent Comments