by DonnaGibbs | Oct 30, 2017 | Books and Children

Breaking the rules

Everyone who is a blogger advises you need to ‘blog’ at least twice a week. I haven’t managed anything like that and there has been an especially long gap since I last wrote. But now I really want to tell you about my new book, so here I am again.

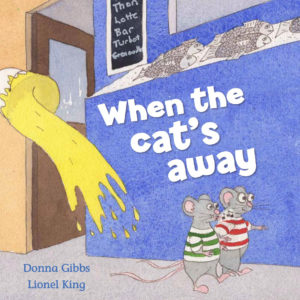

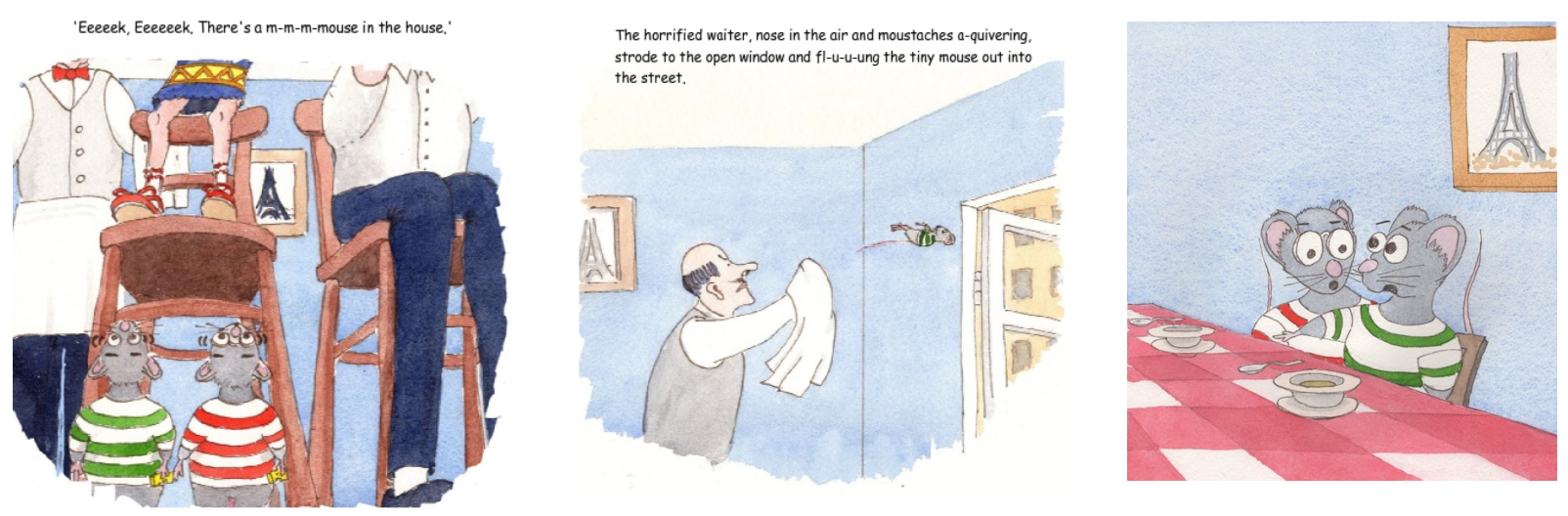

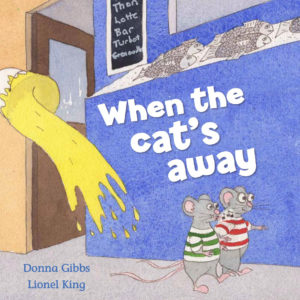

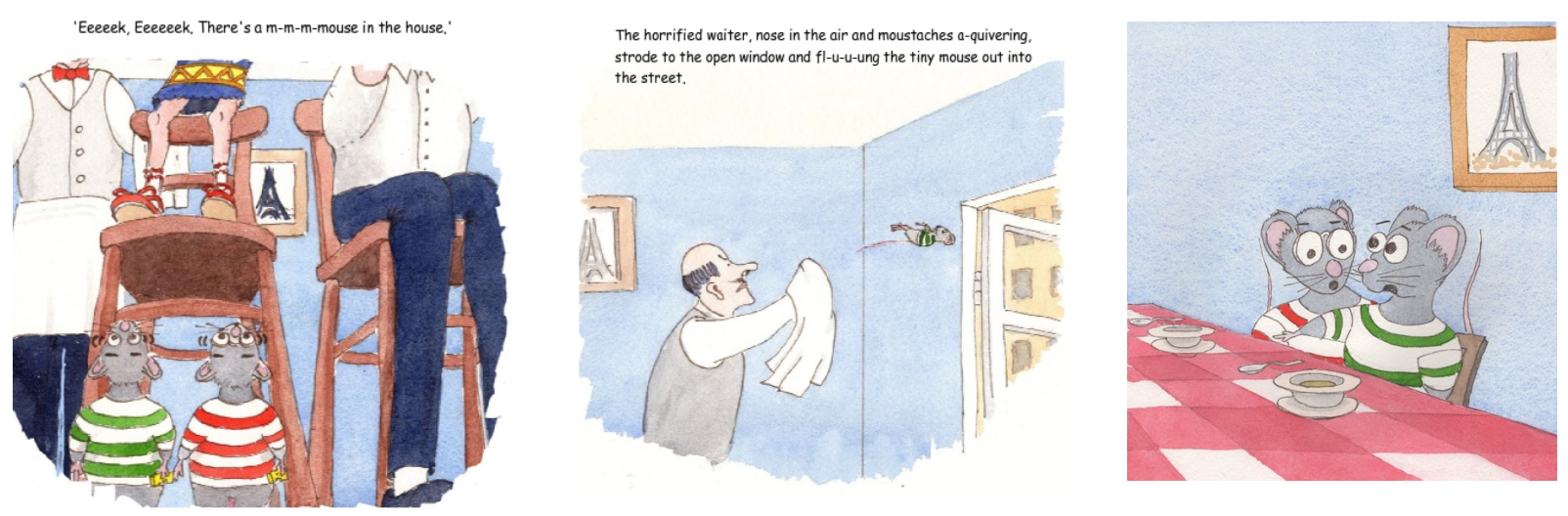

When the Cat’s Away, a picture book for young children, illustrated by Lionel King, was launched on September 25th, 2017.

The launch, which some of you attended, was held at Stanton Library, North Sydney. John McCallum was our impressive MC and Ursula Dubosarsky graciously agreed to send our book out into the world. You can read her speech at the launch here. (Ursula’s kind words will long be cherished by me)

My just-turned one year old grandson, Noah, to whom I dedicated the book (Lionel dedicated it to Judy King, his wife) managed to upstage me as I delivered my speech. You can see him demonstrating his new skills of walking and clapping for the audience.

After the speeches, we had the trumpeter, Mark Strykowski, play the Marseillaise to get people in the mood for the storytelling. I was able to read the story from the online version projected onto the wall in the Conference Room at the library.

The process of creating this book was pure delight from my perspective. Once the text was written it was a matter of waiting for a new illustration to appear in my inbox, usually on a Sunday evening. Lionel is a scientist at RESMED and the weekends are when he does most of his sketching and painting. Numerous conversations followed as we adjusted both text and image until at last our book was ready to go into production.

It is such a pleasure for us to hear about children’s responses to the book. Already we’ve had quite a few comments such as “My daughter (3) woke this morning talking about mice in the house! “. We have also had some wonderful reviews – you can see them on Amazon and at Good Reads (you can ask questions about the book on this site as well) or look at them here. We are keen for more reviewers (only honest reviews) and if you, or someone you know, would like a review copy, please let me know.

“. We have also had some wonderful reviews – you can see them on Amazon and at Good Reads (you can ask questions about the book on this site as well) or look at them here. We are keen for more reviewers (only honest reviews) and if you, or someone you know, would like a review copy, please let me know.

So… if you would like to put the book in someone’s christmas stocking, it is available as a print book from places such as the Book Depository in the U.K, Amazon and the Moshshop. Or you can contact me on my website (donnagibbsbooks.com), or by email (gibbs.donna@gmail.com) and I can post it to you. It is also available as an ebook from Amazon and Smashwords for around $3.00.

In my next blog I’d like to talk about some books that are thought to send the wrong message to children. I’ll be interested to hear what you think.

by DonnaGibbs | Jun 14, 2016 | Books and Children

Children’s learning patterns can seem quite mysterious to an adult. The meanings they take from stories, for example, can be different from the meanings we think they take. In an earlier post I described how children need quite some time to work out what is real and what isn’t; and to come to understand the conventions of form and illustration in picture books – all processes which affect how they construct meaning.

Here are some further things to note:

A child’s logic may not seem logical to an adult. For example: A child might ask the following slightly off-track questions during a reading of The Three Little Pigs:

The Three Little Pigs

Why don’t animals eat themselves?

Why don’t wolves blow people’s houses down?

Do pigs wear hats?

Can pigs walk?

The adult sees these questions as irrelevant to the story being read. But the child has to work through many different connections between ideas and how things work in the world before they come to a similar kind of understanding. Their ‘own’ logic is very precious because it is based on seeing the world through new eyes.

What should you do? Should you interrupt your reading so that the thread of the story is lost and try to answer the questions asked as best you can? I think so. If the child’s mind is actively seeking answers then they really need to know what those answers are.

Of course, some children get so caught up with the questions that you never get back to the story. Maybe if this happens you can suggest you have a turn of just listening to the story. But on the whole questions shouldn’t be discouraged – it means the child is learning to think independently.

Children do not have an automatic understanding of idioms, homonyms and word play. Language has many encoded mysteries which adults understand without consciously thinking about them.

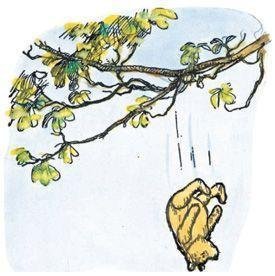

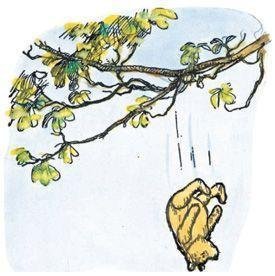

For example, a simple word can cause confusion to a child because it has more than one meaning. I recall the word ‘feet’ causing this problem for my daughter when we were reading Winnie-the-Pooh: ‘Oh, help!’ said Pooh, as he dropped ten feet to the branch below him.’

From Winnie-the-Pooh

But in the picture, as Juliet pointed out, Pooh only drops two feet, not ten! She was convinced the author had got it wrong. This kind of confusion is also caused with idioms.

What should you do? It is probably better to talk about these concepts outside of reading time. You could play word games to help this kind of understanding. Then when they do cause confusion in a reading it will be easier to explain what is meant.

Progress in a child’s learning is not continuously forward and may seem to get ‘stuck’ at times. A common learning pattern for a child is to take a step forward, then a step backward, pause there for a time, then move forward again.

Sometimes, a story a child seemed to understand suddenly raises questions from them suggesting they’ve missed the point entirely. There can be many reasons for this but one is that they become temporarily obsessed with something – not necessarily for reasons we understand. Subjects that regularly come under children’s scrutiny in this way include hands; feet; fathers; mothers; who/what looks after who/what; stealing; eating animals; death; and what’s real or pretend. A child will endlessly test out what can be known about their current fascination – they relate it to everything else – both successfully and unsuccessfully, they imitate it, and they see connections that may or may not be there.

What should you do? Understanding that there are common, seemingly irregular, learning patterns that most children work through means there’s no need to feel anxious when a child seems to ‘go backwards’. It is a part of their learning even though it looks as if it’s the opposite!

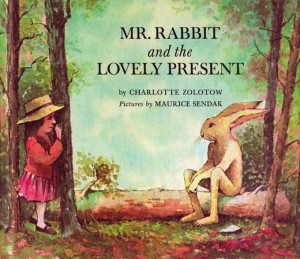

Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present

Children build on what they know of the world by relating it to their books and their books gain in meanings as they learn more about the world.

This is a reciprocal process which reinforces understanding of a whole range of things. In other words, the books you read to children aren’t only offering them the pleasure of story and enrichment for the imagination. They also help build and consolidate ways of understanding and knowing.

What should you do? You can look out for books that might be helpful for situations relevant to your child. There is almost certainly a book that explores every new situation a child will face such as their ‘first time’ experiences – the dentist, the doctor, kindergarten, school – the death of a pet, the birth of a baby brother or sister and so on. It is best though to try to choose well written books that achieve their purpose in imaginative ways as books of this kind can be of poor quality. Do you have any recommendations?

by DonnaGibbs | Mar 17, 2016 | Books and Children

Young children take time to learn whether things are living or non-living, real or pretend. In their world these categories are not yet well defined. It may make for a world that has more exciting, even magical, possibilities but it may also at times be more bewildering, frightening or threatening.

Adults bring to picture books a well-defined set of understandings about how the world works and how the picture book format interprets experience. It takes considerable time for a young child to acquire a similar kind of understanding and ‘background’ knowledge.

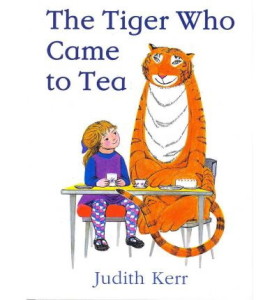

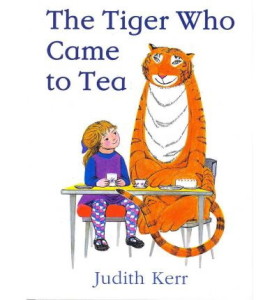

They may know, for example, at one level that illustrations aren’t real and that they represent things from the real world. But at another level they believe that the characters or animals in their books are real. ‘Where did the tiger go?’ asked a boy at kindergarten yesterday when I had just finished reading The Tiger who came to tea. For him, that tiger was out there somewhere. He might even come to visit his house and stay for tea!

Young children take time to learn how illustrations represent things. Adults understand that a partial illustration or a side view of, say, a fox represents the whole fox. A child on the other hand will ask ‘Where are his other two legs?’ and turn over the page to see if they are on the back of it. When I was reading Noah’s Ark to my daughter, Juliet, many moons ago, she thought the ostrich, who had only one leg showing, ‘must have his other leg at the animal hospital where they fix legs.’ (I only remember this because I kept a diary of our reading when she was three until she turned five.)

‘What’s the matter with Mary Jane?’ from When we were very young by A.A. Milne. Illustration by Ernest H. Shepard

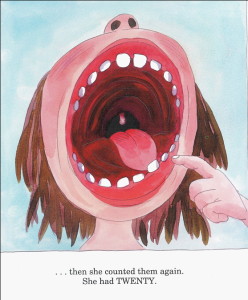

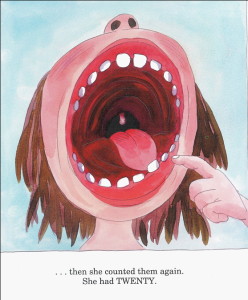

From I want my tooth! by Tony Ross (A Little Princess Story)

A child’s background and experience can also colour what they see. As a child I was sure that the thing buzzing around Mary Jane’s head was a fly. As an adult I came to realise it was her shoe she’d kicked off because of that rice pudding. This had never occurred to me as a way of venting my frustrations as a child though I am sure I hated rice pudding just as much as Mary Jane.

Size in illustrations is another convention that needs to be understood. Children do not always recognise the rules of perspective, for example. A figure who is small and a long way off may, in fact, be larger than a figure in the foreground. Very confusing if you don’t know the rules.

From The Helen Oxenbury Nursery Rhyme Book. Er . . is that a real horse?

Size is also used for other purposes than representing reality in children’s books. It can draw attention to something as does this wonderful illustration from I want my tooth by Tony Ross. The Little Princess’s mouth and teeth fill the left hand page yet on the facing page her mouth is the same size as everyone else’s. Size exaggerates, distorts, creates fear – it achieves all sorts of things in picture books. Children respond enthusiastically to these techniques without necessarily understanding them.

Young children will not yet know the meaning of many of the words they hear when listening to a story. They may not understand enough to ask for meanings and it may take time for them to recognise what they don’t know and to learn how to ask. This plays some part in why children love to hear the same story over and over. As you know, young children love repetition, rather more than you do! ‘Repetition Rules’ has more to say on this subject.

Knowing that each part of a story contributes to the whole takes time for a child to appreciate. It isn’t immediately obvious to a child that a story has a beginning,a middle and an end. After all, many of their earliest board books are not structured in this way. For reasons of their own, young children may be more impressed with parts of a story or its pictures than with the story as a whole.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children need time to come to grasp the concepts that shape what we hear and see which we take for granted. They will find their own way, and they don’t need to be hurried, but it does help if we can support them along the way by understanding the complex processes involved.

Do these observations chime with any you have made? Comments most welcome.

Future blog topics: Please send any topics you’d like me to talk about either by posting here or by emailing me your thoughts (gibbs.donna@gmail.com/).

“. We have also had some wonderful reviews – you can see them on Amazon and at Good Reads (you can ask questions about the book on this site as well) or look at them here. We are keen for more reviewers (only honest reviews) and if you, or someone you know, would like a review copy, please let me know.

“. We have also had some wonderful reviews – you can see them on Amazon and at Good Reads (you can ask questions about the book on this site as well) or look at them here. We are keen for more reviewers (only honest reviews) and if you, or someone you know, would like a review copy, please let me know.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Recent Comments